by Children in Malta

Paul Fuller, Margaret Staples, Linda Tilbury, Mary Whitley, William Rickard, Rita Gauci.

WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

Contributed by edmund_paul People in story: Paul Fuller, Albert, Joyce and Barbara Fuller Location of story: Malta Background to story: Civilian Article ID: A8874615 Contributed on: 26 January 2006

Paul Fuller in Sea Scout uniform at the end of the seige in Sliema

Chap 1 World War II started, for me, in July 1939. My mother in shock and tears, Dad serious but concerned with his next action. We had just arrived in the UK on holiday from Malta and almost immediately Dad was recalled to his job as Sperry gyrocompass specialist in the Admiralty Dockyard there. He was off at once, first to a technical Sperry course, which meant that when he finally sailed in early September. Mum was convinced he had gone down in a ship torpedoed in those first few days of war.

I was eleven and my sister six so we remained in Sheerness until my mother could arrange a trip overland to Malta in December ’39. She, courageously and determinedly, led a group of four adults and three children across France and down through Italy. Crossing the Channel, three of the ladies put their lifejackets over their fur coats until a seaman told them they would sink like a stone. I have never seen women change so fast! Travelling through Italy down to Rome I stood in the corridor and found that a group of German officers, ostensibly at war with us, were in the next compartment. They were very kind to and friendly with a young English boy, pointing out the various sights. From that moment I distinguished between Germans and Nazis. Arriving in Malta, our war was quiet for the next six months and then life changed.

Mussolini declared war on the 10th June and early in the morning of Tuesday 11th we had the first air raids. We lived at Margherita Square, Cospicua and a busload of people stopped outside our house and took shelter with us. Two things stand out in my memory. Someone sounded the gas warning and that was the only time I wore my gasmask — a claustrophobic experience. Secondly, with the passengers I watched Faith, Hope and Charity, the Gloucester Gladiators, doing their stuff almost above us - actually they were over Valetta and Grand Harbour — but it was exciting to watch.

Later that day the UK community around Cospicua was taken to the underground corridors of Verdala — my old Dockyard School — where we stayed for a couple of days with bombs dropping at Verdala. Soon we were on our way to the evacuation camp of St George’s Barracks, northwest of Sliema, where all naval and dockyard families were now billeted. This was to be our home for the next two years, at first crammed into G and H blocks with about twenty families to a barrack room, separated by blankets on ropes; then given our own family room in A block. I went with my father to salvage what we could from Vittoriosa — our furniture and belongings had been stored but had received a direct hit so there was not much left.

Life became a strange mixture of war and peace. The authorities restarted schooling, attempting normality. There was tombola and ad hoc concerts and community feeding in the hall opposite A block. The large white dining hall in the centre was not used for feeding, but, together with the slit trenches around the barracks, was used as an air raid shelter in the ground floor storage bays. School was constantly interrupted by air raids though in time we did not go to the slit trenches (deep trenches bridged by sandstone blocks and covered with earth) until the guns started up. As they stopped, the master would stick his head up and call out that shrapnel was no longer falling, but some boy would throw stones on the tennis court and hold up lessons for a few more minutes!

I had been a choir boy in St Paul’s Cathedral, Valletta before the war and continued to attend where possible by bus from St Georges’, travelling by myself. The shortest route was through Strada Stretta (Straight Street, known to every matelot as “The Gut”) but there was never any trouble for a young boy. However the raids became increasingly heavy and after some particularly unpleasant experiences and one occasion when the bus stopped in Floriana as buildings around were being hit and we took shelter in a house, it was decided that I would stop going (or the choir ceased — I cannot remember which.)

I think this occasion was part of the ‘Illustrious’ blitz. In January ’41 the aircraft carrier limped into harbour for repairs and remained for about ten days. Although I did not know it at the time, part of her trouble was damage to the Sperry gyro compass and my father worked on her day and night for most of time she was at Parlatorio wharf. For this he was mentioned in dispatches. Another of his narrow escapes was only told to my mother long after. He was working against the clock with his mate on a submarine (I think it was the Pandora) in French Creek in April ‘42 when his mate realized he had forgotten a key tool or part. My father was annoyed but they decided to go back for it and have lunch at their workshop near No.1 dock. Returning after lunch they found the Pandora on the bottom. It had received a direct hit.

As a Sea Scout, I was involved in several types of war work. Most of my Scout troop had moved to St Andrew’s Barracks from Senglea [later in the war ( summer ’42 onwards) many UK boys had been evacuated from Malta, so I helped to restart the troop at St Andrew’s and became Troop Leader]. But earlier we became part of coastal defence and observation, visiting Palace and Castille towers for training. Hands-on work was lowly, being on duty and working the hand siren after telephone warnings — usually unnecessary because the planes were already overhead.

In March ’42, our Scoutmaster, Corporal Doug Baldwin was killed, clearing airfields I think. I went to the funeral at the cemetery just above St Patrick’s Hospital on the coast. It is one of my most traumatic memories because as we stood at attention through the service at the graveside, I looked out over St Patrick’s and the sea and watched rows of Junker 87s and 88s coming straight towards us as the guns opened up. I have never wanted a funeral service to end so quickly.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

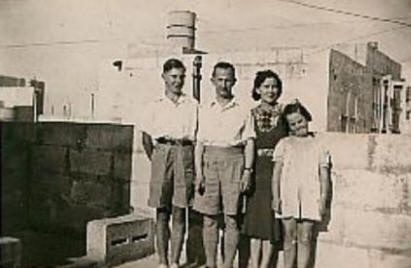

Paul, (Al)Bert, Joyce and Barbara Fuller after the seige, in Sliema

Chap 2 More serious work came after April ’42. The blitz had intensified in ’42 and when the George Cross was awarded on 15th April we were told that Rome Radio had warned that the UK personnel evacuation camps would be bombed. (I have never been able to confirm this and certainly at the time we took little notice) Then on Saturday April 25th the attack came at 7 a.m. My father had a rare day off and we were asleep in the storage area of the central Dining Hall. The din was deafening and as we were near the door in the middle could see the flashes of exploding bombs. Then there was the chilling sound of falling masonry as our own building was hit.

When the raid was over, we walked out to complete devastation. The Luftwaffe had first eliminated the Heavy 4.5-in.and Bofors guns at Spinola batteries across St Georges’ Bay and then turned their attention to the barracks. Almost every building was destroyed. Our Dining Hall shelter, in the shape of a T had received a direct hit on the bottom of the T but the top of the T, sheltering several hundred people, was unscathed. Our own room in A block had a direct hit and we began the task of salvaging what was left. I remember my father saying all four of us are safe, so don’t worry about our possessions. During the course of that day and the next two or three, between rushes to the shelter we collected bits and pieces. My father’s half-hunter watch was hanging on a hook on the first wall that was standing five or six ‘rooms’ away. The mah-jongg set had been near the bomb and we began to find pieces all over the barrack square. It became a joke among our helpers and we found all except about five pieces!

We were billeted temporarily in the moat of the fort half way to St Andrew’s Barracks but the conditions took their toll on our health and first my mother and then I were carted off to Imtarfa Hospital with enteric fever. It was fascinating for a young boy, almost 14, who as he recovered, stood with forces personnel looking out over Ta’ Qali airfield watching the intense bombing and the recovery, as Spitfires were flown in, swiftly re-fuelled and armed, and joined in the fight. They shot down a number of bombers in front of us and we had a grandstand view.

The family found a flat in Point Street, Sliema in May ‘42 and my second and third type of war work began. During March the convoy known as MW10 had arrived from Alexandria after intense attacks. Talabot and Pampas were sunk in Grand Harbour as they were being unloaded. There was criticism that the unloading was taking to much time, so it was decided that future convoys would be unloaded swiftly to dumps around the island and supplies would then be redistributed. I was asked with other Scouts to guard the food dumps which would be subject to pilfering, so as Convoy ‘Harpoon’ arrived in June I went on night duty. Armed only with a Scout staff, I am not sure I would have been any good stopping a determined attempt but although we saw movements and heard whispering, we were not attacked. My task was to guard Pink Dump though I have no idea where that was.

Finally, I was told of another convoy about to arrive, we hoped. This was the famous ‘Pedestal’ Convoy and as the ships began to arrive in August ’42 I was sent to ‘P’ point at the Marsa, near Corradino. I worked from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. as a telephone boy on Operation ‘Ceres’. As a tug towed lighters round to my wharf, my job was to record the tug and lighter numbers and report their arrival to HQ. HQ then told me which ship to instruct the tug skipper to return to. As all the ‘stevedores’ were UK forces personnel I got on well. There were few UK people left and though I had many Maltese friends and liked the Maltese very much, it was good to talk English. Unfortunately there was not much food landed at P point — it was mostly ammunition, fire engines and the like. I remember sitting on a pile of bombs talking to resting soldiers as we waited for the next tug. But for some reason the raids were light and the smoke screen helped us. However, that same smoke screen entered the lungs of my Uncle Allan, Chief Engineer on the Brisbane Star, there in the harbour with a huge hole in its bows. He eventually died from it.

For that job I was paid ten shillings a day for ten days — my first week’s wage. (When I entered the Admiralty Dockyard a few months later as an electrical apprentice, it was two shillings and sixpence a week.) I collected some guilt as well, for the Maltese Scout colleague who took the night shift relieved me early and was in turn relieved late because my only transport was the ‘dockyard bus’ which took UK personnel from Sliema to the Dockyard.

The siege continued for a number of months — in fact it became worse in terms of shortages. My sister and I went to bed hungry most nights, but our parents were hungrier and the armed forces were even worse off. On the black market eggs were 2/6 each — I think about one twentieth of the average wage. We lived by Victory Kitchens for our main meals and remained without light or cooking facilities. I continued to help run the Scout Troop at St Andrew’s and remember one occasion when, crossing a football pitch (against rules!) we threw ourselves to the ground as an enemy plane strafed the barracks. The final scary blitz was in October and the relieving convoy arrived in November. I started work in the dockyard on 7 November but that month the siege was over.

It was a strange start for an apprentice. Sunken ships everywhere, the destroyer Kingston on its side in No.4 dock; the wreckage of cranes spread across the roads, collapsed buildings all over the Yard. The only toilets were cubicles overhanging the dockside with water pumped through them. But the Yard kept going and I became proud of being part of the effort to keep the Navy in service. The final excitement was, as an electrical apprentice, during a strike, sailing on an MFV to one of the aircraft carriers out at sea to carry out repairs. It was part of the fleet assembled there to invade Sicily. My war was almost over.

Paul Fuller

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Contributed by medwaylibraries People in story: Pat, Edwin, Margaret and Daphne Staples, Major and Mrs H.W. Staples Location of story: Malta: Floriana and Valletta Background to story: Army Article ID: A7075578 Contributed on: 18 November 2005

Major and Mrs H.W. Staples, and their four children - Pat, Edwin, Margaret and Daphne outside their home, Dragona, shortly after their arrival on Malta in January 1939.

My memories of Malta during the Second World War by Margaret Hutchinson (nee Staples.)

My father’s job

When my father Major H. W. Staples R.E. (known as Sam) left the army in 1949, a letter came from the War Office saying, “I am commanded by the Army Council to express to you their thanks for the valuable services which you have rendered in the service of your country at a time of grave national security.” This made me realise that my father played an important part on the island of Malta. He was the Deputy Commander of the Royal Engineers for the southern part of the island covering the main harbours and aerodromes.

It is easy to forget just how close Malta came to defeat between 1940 and 1942. I arrived in Malta with my parents, two brothers and two sisters in January 1939. At nine years of age it seemed like a new adventure — little did I realise that it would be six years before I left the island in March 1945.

Island at War

My memories are of fear and starvation but also of love for the people and the island. At the beginning when the Italians declared war life was difficult, but when the Germans started bombing only sixty miles away from Sicily, it was horrendous. It became one of the most heavily bombed places in the world.

We all slept in the shelters and spent most of the day there too. As convoys fought to get through with supplies, they were pounded by the enemy. Without the RAF fighter pilots and anti-aircraft personnel, Malta could easily have succumbed.

Scarcity of food

I remember my father telling me that there were only 10 days’ supplies left. As our ration at the time was very limited — only one slice of bread each per day — leaving the table hungry wasn’t unusual. My poor mother struggled to feed us — I remember she became painfully thin, and began to look old. My father recorded he lost 8” off his waist and felt quite fit except when walking quickly his heart beat sounded like a going in his ears.

How our poor dog Handak survived I don’t know as he was ordered out of the dining room when my mother realized we were slipping titbits under the table. The poor dog was hungry too. First our canaries died and then the chickens (no doubt a meal was made of each hen). They stopped laying for lack of food although the gate to the chicken run was left open so they could find what they could in the garden.

I used to queue at the Victory kitchen in Floriana for our one meal a day. Divided between seven of us, it was pathetic; maybe enough for one and a half people — but I must say, it was always very tasty. My mother learnt to serve it on small plates. One day my father acquired a sack of oatmeal riddled with weevils. My mother asked me to try and clean it — an impossible task — so it was cooked with the weevils! My sisters and I played “loves me, loves me not” with weevils rather than fruit stones.

I went to the market in Valletta with my mother — most of the stallholders had left but there were still a few there. We came home with a fish that had cost a pound — a lot of money in those days. I think that it was that day that the Opera house was bombed and we picked our way through the rubble. Running from one shelter to the next became the norm.

Operation ‘Pedestal’

Operation Pedestal was launched to help Malta when we were at our lowest ebb. Of the fourteen ships that sailed nine were sunk and in the early hours of August 15th the freighter “Ohio” limped into the Grand Harbour lashed to the side of other vessels. We children used to rush to the bastions to cheer and wave them in. When supplies arrived only to be destroyed during their unloading in the grand Harbour, the island’s morale was severely hit. Both my brothers, Pat and Edwin were detailed to go to the harbour wearing their Boy Scout uniforms, to help supervise unloading and stop pilfering.

A terrifying experience

One day returning from Chiswick House School in Windsor Terrace, Sliema, my sister Daphne and I arrived at the quay and as the ferries had stopped running we had to rely on the dghaisa — a boat rather like a gondola — to take us across to Valetta. There had been raids all morning and we were desperate to get home. Our lessons had been in the shelter and as it was about half past four and we hadn’t eaten a thing since breakfast we were feeling terribly hungry. Soon the little boat was full of Maltese women and children gesticulating wildly and a Maltese soldier of the K.O.M.R. was giving a full account of the morning’s bombings to one of the boatmen.

Soon we were on our way, gliding over the water — but alas! We had just reached the middle of the harbour when the siren wailed out mournfully. My heart was beating wildly and I prayed that the red flag would not be hoisted until we reached the other side. This was raised above the Castile when the raid was directly overhead. One woman began screaming hysterically and urged the boatmen to go faster, faster! Beads of perspiration poured from them as they pulled at the oars and we watched, waited and prayed.

Suddenly the red flag was hoisted and we realised our prayers had been in vain. One old lady threw herself on the bottom of the boat sobbing and begging the saints to take care of us all. My sister turned dreadfully pale and I thought she was going to faint as she usually did in such circumstances. She clutched at my hand and we gazed above scanning the blue skies for the approach of the enemy. A dozen or so planes passed over and we presumed they had already dropped their bombs on the other side of the island. Our guns opened up and the planes made a speedy exit. “Raiders passed,” blared out and as we reached Valetta we all breathed a prayer of thanks. Slowly we made our way up Great Siege Hill homeward bound. A few minutes passed and the siren wailed again. As there were no shelters close by we made our way to a small gap in the bastion and huddled in. A sailor and two Maltese soldiers joined us and after a while the sailor assured us the raid was practically over and we could continue our journey. We thanked him and began to run up the hill.

Before we had gone 200 yards the guns began to bark and I could see three planes coming in our direction. I screamed “Run Daphne — make for that wall” and we ran as fast as our legs could carry us. There was a loud whistle and them WHAM. The ground shook violently and when I had the courage to stand up the air was full of smoke and dust. Daphne was lying in a clump of daisies quite a few feet ahead of me where the blast had lifted her. I thought she might have been hurt but was assured it was only fright when she stood up and started screaming.

An English soldier popped his head out of a slit trench, ran over and picked her up in his arms and shouting for me to follow, ran back to the slit trench. I felt terribly giddy and slowly made my way to the shelter. The raid was over 15 minutes later and at last we resumed our journey undisturbed.

A few days later my father told me that two Maltese soldiers had been killed by enemy action less than 100 yards from the spot we had occupied. I shall never forget that day as long as I live.

Most British families left the island early on, some going to South Africa for the duration, others going around South Africa back to the U.K. When my father asked my mother to leave before the bombing started, she said, “No — we stay together”, and so it was, and she wouldn’t be moved. One day I was out in the open during a raid with my mother and sister Daphne, and I remember shouting, “Dear God, I’m too young to die.”

The award of the George Cross

Malta withstood 3,340 alerts and 29,674 private dwellings were destroyed or damaged.

King George VI was the first of several distinguished visitors followed by General Montgomery and General Eisenhower. The Pavilion in Floriana was renamed Montgomery House when he moved his headquarters to Malta.

The island of Malta was awarded the George Cross By King George V1 on the 15th of April 1942. My father often said to us children that “each of you has earned a part of that George Cross.” Thank God my family survived, but it is an episode of my life that I will never forget - would you?

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Saved by a Wellington Bomber. -

Contributed by ElderlyEsmerelda. People in story: Linda Tilbury, her sister Clare and their parents Harry ('Tilly') and Margery Location of story: Malta Article ID: A9032087 Contributed on: 31 January 2006

A Wartime Adventure experienced by seven year old Linda Tilbury

When the WW2 broke out my family was living on Malta. My father worked for Barclays Bank (D.C.O.) and we lived on the seafront in Sliema. My younger sister and I went to Chiswick House School which was nearby. From our house we could watch brilliantly painted cargo boats sailing to and from Gozo, and the great variety of naval vessels going in and out of Grand Harbour,Valletta.

The years leading up to the War were very happy for us, as life in Malta was pleasant for civilians as well as those in the Services. Once Italy entered the War however, things changed rapidly as the fight for Malta began. From our house we watched dog fights in the air, the dramatic sight of a Gozo boat being blown up, a German pilot parachuting slowly down into the sea just off-shore, and most exciting of all one morning early, a famous chase of German E-boats out of Grand Harbour.

Our larder was sandbagged and made into a shelter, and we kept the Rediffusion on all day for the early air-raid warnings. I can still remember the staccato "Signal-al-attaqit mil aiero", or so it sounded to me, with the relief of "Aieroplani tal-ado adaou" as the raid ended.(Forgive my poor Maltese).

One day in February 1942, while my sister and I were at school, our house received a direct hit. Both my parents were at home, and luckily, apart from shock, were unharmed, but our neighbour, an elderly retired headmistress called Miss Yabsley had been standing at her front door, and she died from the blast. The bomb sliced through our house and hers, leaving a great gaping hole. There was generally very little fire damage, so we were able to salvage most of our belongings and store them.

From that day for the next three months we moved from place to place, bombed out each time. First we went to the Plevna Hotel, and spent our nights in the nearby old ammunition tunnel at Tigne Barracks. It made a safe if damp and dismal shelter.

The Plevna too was hit, and we searched the rubble for passports and suitcases, and moved to another barracks up the coast at St. Patricks, where we had a quarter above a NAAFI and had to use the nearby slit trenches when there was a raid...horrid and unsafe. Once more this quarter got a hit, and by now my father was getting anxious about our safety. Food was very, very scarce, and unvaried..I can only remember pork, cauliflower, tomato paste and Halva-ta-Turk, the sweet nougat-like paste made of sesame seeds and sugar water. School was out of the question as the raids were so frequent.

Our last move was to another Hotel, the Metropole, in Dingli Street, in front of which was one of the deep shelters dug into the rock with small niches off a central corridor for families to have bunks to sleep in. Luckily we had a friend who had paid for one of these cubicles.. airless and humid, but safe at least.

Meanwhile my father must have been busy seeking some way to get us away from Malta. The award of the George Cross to Malta in April 1942 was encouraging, but it didn't stop the continual noise of heavy artillery, the whining of shells and bombs, and the worries about food and safety for everyone.

There was no way we could leave by sea, as all civilian shipping and air transport had long ceased. Somehow my father was offered the chance of a lift from the R.A.F. at a time when increasing numbers of Fighters and Bombers were coming through Malta to refuel en route to North Africa.

One night at the beginning of June we were told to get to Luqa immediately. We walked out to the runway where a Wellington Bomber was parked and there were hasty goodbyes as we climbed in and flew off into the night. I cannot imagine what my parents must have been feeling at that moment. My father went back to his job, and waited for news. He had to wait 6 weeks to know if we had made it or not.

What happened in the next few hours was clearly momentous to a lively girl of seven years old. By great good luck, the carbon copy of the letter I wrote to my father from Cairo within days of our safe arrival has survived. It described our flight and the kindness of the crew, and the excitement of a huge English breakfast. My father must have shown my letter to the person who had helped to get us away, and it was at Luqa that it was typed out and the top copy pinned on the Notice Board there. The carbon copy, which I treasured for years, is now in the Imperial War Museum, along with a photo of my mother, sister and me in Cairo not long before we were lucky enough to get passage to safety in South Africa.

The troopship was The Monarch of Bermuda, and it took three weeks to make the journey as far as Durban, where we had to disembark. I have since met by chance a woman who with her sister and mother was also on the troopship, and has letters from her mother back to her father in Cairo describing the journey in the great heat of July and August 1942.

There is more to this story should anyone wish to contact me, as there is not room today to quote the letter I sent. The war certainly made a huge difference to the lives of children like us, as we adapted to new places and went without any formal education sometimes for months on end. I am conscious of having been most fortunate in my parents, and of the privileges of being British at that time.

Linda Tilbury

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Contributed by cornwallcsv People in story: Mary Whitley Location of story: Malta Background to story: Civilian Article ID: A4661769 Contributed on: 02 August 2005

This story was entered onto the Peoples War web site by Rod Sutton on behalf of Mary Whitley, the author, with her full permission. She fully understands the terms and conditions of the site.

I was born in Malta three years before the second world war started, but I have vivid, unpleasant memories of some of the things we went through in Malta during the war – in fact, to this day, I cannot and will not watch a war film. Also, a lot of things my parents did at the time seemed strange to me.

The first strange thing I remember, soon after war was declared, was dad digging up part of the back garden – going quite deep and lining this big hole with waterproof sheet. A few days later the garden was back to normal with shrubs where the big hole had been. I asked a few times why the big hole and when did dad cover the hole but I never really knew why until after the war. Mum said they had to try to stock up on imported items like tinned food and matches and kerosene as all the Maltese knew that Malta would be heavily involved, being a British colony and strategically positioned, and we would not be able to get any imports. It became illegal, in Malta, for people to have large stocks of imported items in the house and a government inspector did go around the housed checking for large stores of food etc. Of course, ours were not discovered. Dad filled in the hole with stores of household needs, at night, while my brother and I were asleep.

As predicted, everything became scarce and rationing was introduced. We had to queue for hours at every shop we went to because the rationing cars had to be checked etc. etc. Foodstuffs became very scarce – even locally grown vegetables, as a lot of farmers were disrupted by the constant bombing. During meal times my mother always pretended she was not hungry, so dad and the children would not do without.

I remember one other incident, which, to me, did not make sense. Mum accidentally knocked a pot of soup off the stove and she cried and sobbed and made such a fuss, which to me seemed totally out of proportion. What I did not realise at the time was that the pot contained all the meat and pasta etc. that we had before the next rationed allowance was due. I can even remember the dress my mother wore then as she cried. Luckily, my dad had very good contacts with army officers (he was attached to the REME as a civilian) and he would bring home tins of bacon – I can still see this bacon which came out of the tin like a small kitchen roll. Dad also brought tins of ship’s biscuits and bars of chocolate. Mum used to melt the chocolate and use it instead of butter on the biscuits for a packed school lunch. Of course, other pupils would not have a lunch pack and my brother used to have his stolen from his satchel nearly every day, and he would be brought to me at break time so that I could share my biscuits with him. I used to keep mine in my desk even though that was against teacher’s orders. The cries of hungry children is with me to this day and I now get so much pleasure from watching children eat.

School was more a series of ‘in and out’ of air raid shelters, especially towards the end of the war, when Malta was being bombarded day and night. Public shelters had a few small rooms (no doors) and people could hire a room. My dad hired one of these rooms and he put bunk beds in there so that my brother and I could sleep at night. Most nights were spent in the shelter. I must have slept quite well on my bunk because I do not remember much about the nights in the shelter. I remember a lot of prayers being said by all the people packed together in the main area. There was no seating, but most people took seats from home to the shelter to sit on during these nights.

I also remember my brother being punished for leaving the garden door open once, when we had lights on in the room. We had to black out all doors and windows, so nothing was visible form outside after dark.

As service bases, airport and harbour areas were so heavily bombarded that the residents were evacuated and were sent to live inland with other families. We lived inland, so we took a young cousin of dad’s and her husband and they used my bedroom as it was next to the bathroom. Naturally, I did not like that and hardly spoke to the couple when they were in the house. The girl spent a lot of time with her mother during the day, so they only came in to sleep after the husband finished work and I would not speak to them because they were going to ‘my room’. I felt very deprived.

One other sad thing I remember is my father coming home from work and saying that there was no more food left on the island as the ships with provisions were all being targeted by the Germans and sunk off Malta. Dad could not have realised that I was listening. This frightened me so much and I must have thought we were all going to die soon. I told all my friends at school and the teacher was very angry with me for saying such things. I asked my mum what would happen if we did not eat for a long time. For days I waited for mum to tell us that she had no food for us. Fortunately it did not happen and when, at last, a ship with provisions managed to reach Grand Harbour with little damage, there was so much jubilation in the street I was, once again, baffled by the behaviour of the grown ups.

As there was no winter clothing left in the shops, people were making coats and jackets out of blankets and old army greyish/khaki blankets were much appreciated by any family. My father managed to obtain a white blanket from the army and my mother made me a coat out of it. She put lots of embroidery on it to camouflage the material and big sky blue buttons and a matching big ribbon below the collar. I remember her threatening to punish me if I told anyone it was made from a blanket. I also remember my mother making us summer sandals from rope and bits of old heavy cottons. Dad made the soles from a piece of rope stitched together and mum made cotton straps for the top of the sandals. I did not like them at all because the tied up straps hurt my legs. They tied up like Roman sandals and sometimes the criss-cross straps pinched my toes.

By the time war was over a lot of school children were ill from malnutrition and I even have the sad memory of one of my class mates being injured when a bomb went through their house before they had time to go to the air raid shelter. It was a long time before things returned to normal because of the effects of all that devastation and deprivation, both physically and mentally, on the population of Malta.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Contributed by ElderlyEsmerelda People in story: William Rickard, his parents and brother Location of story: Malta Background to story: Civilian Article ID: A9009399 Contributed on: 31 January 2006

In those extraordinary times the adults at St Georges barracks — mostly evacuees from the bombing themselves — worked hard to give us children ordinary experiences. We had a rudimentary school and this Robin Hood scene is from an entertainment organised by Mrs Oakford in 1941. I am second from the left.

Schooldays during the Malta blitz. Bill's story.

I arrived in Malta by boat, with my mother and little brother, in January 1938 and lived in a flat in Senglea. My father, who was an engineer, had arrived about six months earlier to take up a post in the Malta Dockyard. When the war really began there in June 1940 we were told to go to the Dockyard School, where I was a pupil, up on the bastions behind the Three Cities. It would be safer there as we could shelter in the underground storerooms that seemed to us like dungeons. We had already rehearsed this some time previously and thought it was a joke, but this time it was different.

One evening a heavy raid was in progress. My father and his friend were having a drink on the way back from work when a bomb dropped across the road from the bar demolishing a house and trapping a mother and two children, but fortunately they only had cuts and bruises. My father and his friend released them and brought them to our ‘dungeon’. A few days later we were moved to St George’s Barracks further up the coast, away from the dockyard area, where school was infrequent, about three days a week, but swimming was high priority! Some months later we moved back to Senglea. The raids were not too bad until January 10th 1941 when we watched the aircraft carrier Illustrious glide in, knowing that it had been in a battle as we could hear the gunfire earlier in the day. Then the German planes arrived and the raids got heavier and more frequent.

January 16th 1941

On the 16th I was at school in St Georges Barracks at around 2pm when the alarm sounded. We went to the shelter which was a roofed-over slit trench but as usual we children sat on top of the sandbags round the entrance to watch the dog-fights. It was when the planes were over the Grand Harbour that we could see them peel off and dive down one by one. We knew that they were Stukas and what they were after. They were determined to finish off the Illustrious. We were sent home in the lull between air raids, dropping children off the bus on the way until my journey finished at the Dockyard gate.

When I got to Senglea it looked as if every house had been hit and as I climbed over the rubble in Two Gate Street I feared the worst as my mother and brother were there and they didn’t always go to the deep shelter round the corner, but this time luckily they had. Our flat had been hit and there were big holes in the roof and balcony. Dad arrived and said "Take what you can carry, we are off to St Georges again." He then went back to work and we never saw him for three days as he was working on the repairs to the Illustrious. By some miracle the ship was not hit again and she slipped out safely on the Sunday night. The raids continued, four and five a day, long and heavy but we still swam most days for the next five months!

July 26th 1941

I was woken before daylight one morning by gunfire although no warning had sounded. I looked out and could see tracers from the ack ack battery at Spinola going across towards Grand Harbour in the distance. Thinking that I would see more I climbed up a tree in a field just in time to see a terrific flash and debris flying into the air. We later found out it was Italian fast boats packed with high explosives trying to breach the breakwater and boom defence to let midget submarines into Grand Harbour. But none of them made it.

That tree was still there in 2004! The raids continued but were not so heavy.

January 1942

The Germans were back with a vengeance, regular as clockwork, day after day, punctually at breakfast, mid morning, lunch, afternoon tea time, then it was the night bombers' turn. It seemed that a form of carpet bombing took place which culminated in the St George's barracks being attacked on a Saturday around 26th April which was my brother's birthday. Our room was blasted so we had to pick up whatever we could salvage, but my piano had been destroyed. We were allocated another room in another barrack block and the raids eased off again.

Some days we helped the gunners nearby, filling the bren and lewis gun magazines with live ammunition — two bulls then one tracer, two bulls one tracer, perhaps 30 rounds.

June 1942

My father was informed that families were going to be evacuated and that we had to be ready at a day's notice. So one afternoon he arrived "home" and said we had to be prepared to leave that evening. A car came and we set off for Luqa airfield. After about 2 hours an RAF officer told my father that the plane had not arrived so it was back "home" again. Some time later we once more set off but this time it was postponed due to a heavy raid which lasted nearly to daylight, so back "home"! The third time we boarded the plane and got settled, then a fuel leak was discovered so once more it was back "home" yet again. Attempt four, no problems. We took off in a Lockheed Hudson, a medium bomber, landed in the desert somewhere to refuel then on to Heliopolis, Cairo. We stayed there for two or three weeks then went to Port Tewfik for another two weeks. There we boarded the Monarch of Bermuda, sailed round the Cape, and after stopping at various ports ended up at Gourock in Scotland in August 1942 when I was 12 years old.

Sometimes we were frightened but usually the excitement took over. We did things that no children today are allowed to do, but then we were fireproof weren’t we!! Looking back to those days I feel privileged to have lived in Malta at that time. It taught me about war, the good times and the bad but mostly the stupidity of it.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Memories of an English Childhood in Malta -

Contributed by maltesecockney People in story: Rita D. Salmon nee Gauci Location of story: Malta Background to story: Civilian Article ID: A4452743 Contributed on: 14 July 2005

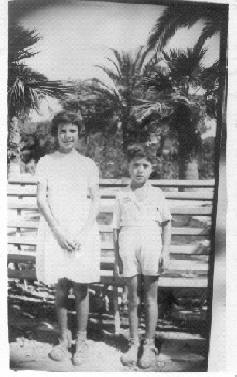

Victor and Rita Gauci, taken in Saqqajja Park, Rabat, Malta 27 July 1942

Chapter One

During the summer of 1938 my Father decided to take us to his family in Malta. He thought we would be safe.

We travelled by ferry to France and stayed overnight in a hotel on the front at the seaside. I remember we had fish in aspic for supper and boiled eggs for breakfst. The eggs came in a glass with sugar!

In the bay there was a flying boat, the first one I had ever seen.

We then went by train over land through France, Switzerland and Italy. There were soldiers waiting on all the platforms. We must have been travelling third class as the seats were slats and very uncomfortable. When we got to a port in Italy we went across to Malta by ferry. It was terrible weather and I was very sick. One of the stewards gave me a drink of Sal-voltili and took my mother and I into a cabin to lie down.

I remember how wonderful it was coming into the harbour, and the blue harbour lights and wind on my face. We rode in a horse and trap to the family home and stayed with them until a suitable flat was found for us all. The family had very little English and Nana and Nanu none at all. Only my father was able to do all the interpreting and we got by with signals.

In 1939 I remember sitting on mums bed with my sister Rosie and my younger brother Victor, not quite knowing why we were frightened, until mum said, "The war has started."

It didn't mean a great deal to me, probably something exciting was about to happen. Little did I realise what was about to be unleashed on our lovely island - not realising that the air defence consisted of three workable planes, called Faith, Hope and Charity.

We had moved to the farming country near St Paul's bay. My father was stationed nearby and was able to come home. We moved again. Mum said she had never moved so many times. In all we moved house thirteen times. At the time we were at Ghain Tuffieha, we had some of the heaviest raids.

Our house had two rooms and cook room and WC. My father had dug a shelter in the rock-side and we played and slept in there. Most of the local farmers lived in natural rock caves. We had long bunks along one wall and we slept head to toe. The lighting was small clay lamps with a wick hanging out of the spout and once we were in there we children never went out.

When the raids were further away we watched the Italian fighters and bombers coming over and counted the planes. They came in fives or sevens. If they got too near we were soon in the shelter.

My brother and I were playing away from home one day and we were caught in a raid, it was overhead so we lay along a field wall. We could see the machine gun bullets from the Italian fighters along the path. I was more afraid of the ants that were in the grass above us.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Chapter two

Our water came from a well and had to be boiled and there was also a tap some distance away, with the slogan 'waste not want' engraved on the tap.

We were counted as civilians as father was in the Kings own regiment, which was the Maltese Army. So as the war progressed and food got shorter we were in rather a difficult position. The local farmers were able to live off the land and we could buy food from them or the local village shop. But as the food got shorter the farms had all the produce confiscated for the Victory kitchen. We were friends with the entire village and they helped all they could. Mum would make them cakes when any flour was available and knit in exchange for fruit or eggs.I would go round the villages to families with a baby and goats: in return for rocking the baby in the hammock I would get a cup of goats milk. My father had an arrangement with the cookhouse that he would have whatever rations were available to him for the week and he would bring it home. Mum would eke it out fro the five of us. Fathers typical ration was a tin of corned beef, a tin of herrings in tomato sauce. Perhaps army biscuits, which were hard biscuits called hard tack. He would also barter for food, the farmers were desperate for machine oil for the water pumps for the fields. My father was able to get a small can of oil with about a cup full of oil and the oil went all round the farmers so they could all oil the pumps.

The food situation was getting very bad although the offical ration initially was a loaf of bread, 3oz of fat, 1.3/4oz of cheese, 1 1/4oz coffee, 3 pints of milk, 3lbs tomatoes, 1.1/2lbs of potatoes and 8 gallons of water. No sugar, rice, pasta, tea, oil, butter, soap or meat and fish. This was of course if you were near enough to a town or village with a supply. I remember walking three miles once for a small loaf of bread. All the confiscated food was given to the Victory kitchens to be made into soup. We visited an aunt and I went with her for a bowl of soup. It was very meagre and had very little in it. It looked like clear soup to me. Aunt said it would be good for me!

It was sad to see all the barns empty and even the chicken pens, as there was no food for them. the goats were always taken out to graze anyway. Even in the worst of the bombing the shepherd went out with the goats and was able to to shelter in one of the caves. I never heard of any goats being killed.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

Chapter Three

We were visiting my grandparents and were all billeted with different members of the family. My brother and I were with my grandfather Nanu and he bedded us down with him in some catacombs. He had rented a room! The catacoombs were small sections cut in the rock well below the surface of the ground. During the night I needed to go to the toilet and I didn't know what to do, so I ran up the steps, all hell had broken loose, bombs, guns, lights and I was terrified. I turned around and came back down the the stairs and wet on the stairs. No one took any notice they were all so busy. I don't know where my big sister or my mum was and all the other grown ups in the shelter appeared to be asleep. I don't think I have ever been so frightened.

One christmas 10 soldiers from the camp in Ghain Tuffiegha came to our home with their dinners and mum shared it out between us all.

That year 1942 I had a book given to me called The Jungle Man and His Animals by Carveth Wells. I didn't know the soldier but his name was Sgt Marshall. I know I had to write and say thank you. I also had a dolls house my dad brought home, that one of the soldiers had made, all the doors and drawers opened.

The camp cobbler made us hob-nailed sandals and mum knitted us rope-soled sandals. We rather liked the hob nailed sandals as they made a lovely loud noise.

During one very big raid on the army camp several of the soldiers were killed. At that time I was coved in scabies and had to go to the camp Doctor, who would soak the bandages off my arms and legs (mum had to boil the bandages), then he would cover the sores with sulphar ointment, made with lard, which we had to supply. None of the rest of the family caught scabies. But when we came back to England the whole family had to go to the cleansing station and have disinfectant baths and then we were all painted with lotion, which smelt of almonds. Very effective but a great indignity for my big sister and mum.

There was also a naval rest camp at Ghain Tuffiegha, the sailors were off the battle ships and I remember were all in a very sad state of shock. They were very kind to us and would come to see mum and tell her all about what had happened to them. They would bring a bar of soap or chocolate when they had any.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.

How you can use the content

The stories and images in the WW2 People's War archive have been contributed by the public and copyright rests with the authors, although by registering on the site they have also given the BBC a non-exclusive right to sublicense and use this content. Find out more about the terms under which this content was added to the original site.

If you wish to use the content in a commercial context (eg a publication, CD or website the public needs to pay for to obtain, or a project such as a broadcast series or film), please contact the BBC to obtain permission. Use the Contact Us link on the left hand side of the page to do this.

If you wish to use this content under 'fair dealing' terms - eg as part of a non commercial project such as an educational research project or a cost-recovery project such as a public exhibition or publication, you may do so, but should acknowledge the provenance and copyright holder of the content in the following way. On a credits / acknowledgements page, or in a prominent position if used as part of a display:

'WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar'

Each entry or extract should be credited by name / site name eg 'John Smith, WW2 People's War'

Material should not be used for political or lobbying purposes or to raise funds. If you are a political party, or affiliated group, or a charity, and wish to use content from the archive, please make your request directly to the BBC using the Contact Us link.

Users agree to respect and maintain the integrity of the image copied, and not distort, amend or mutilate the original material. Original text and images should not be modified or adapted into a derivative work such as a film or artwork. A series of unmodified extracts can be used, ie assembled into a collective whole, but content from the archive should not amount to more than 20% of your site or publication.

Use of content from the archive does not give you any sublicensing rights. Any organisation or individual who wishes to use the content should be aware of these guidelines and use the content directly from the site.